A new working paper from World Bank economists looks at the sukuk space from the point of view of development: that is, where compliance with Islamic principles is important for much of the population, impediments to a sukuk market becomes impediments to economic development.

A new working paper from World Bank economists looks at the sukuk space from the point of view of development: that is, where compliance with Islamic principles is important for much of the population, impediments to a sukuk market becomes impediments to economic development.

The authors [Ketut Ariadi Kusuma, senior securities market specialist, and Anderson Caputo Silva, lead securities market specialist] maintain that certain problems associated with the issuance of sukuk, an instrument in Islamic finance, do impede broader development, and they propose that policy makers in affected countries “use a framework similar to that of the development of conventional bond markets” in order to remove this impediment.

One idea in particular that stands out, because it is stressed here more than it usually is in such discussions, is the role of money markets as enablers of sukuk.

What the Sukuk Space Looks Like

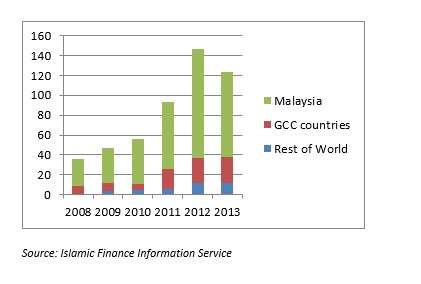

Kusuma and Silva say that $147 billion in sukuk bonds issued in 2012. The level of issuance in 2013 was somewhat below that, at $124 billion, a dip in the long-term growth trend. The World Bank authors explain this as due to the period from to September 2013 when the fixed-income markets globally suffered from an anxiety attack over the U.S. Federal Reserve and its announced intention to “taper” its quantitative easing policies.

The graph below, adapted from Figure 1 in the report, gives a more vivid sense both of the long-run trend and of the 2013 dip.

Breaking it down by nation, more than two-thirds of the global sukuk market consists of bonds issued in Malaysia. In 2012 for example, this was the source of $110 billion out of the $147 billion total. Another $25 billion came from the Gulf Cooperation Council region, the remaining $12 billion from, well … the rest of the world.

A Statement of the Problem

Impediments to the growth of sukuk markets include: the lack of standardization of structures and practices; issues surrounding insolvency and investor protection; and the lack of liquidity.

On the first point, standard setting bodies do exist. Unfortunately, there are too many of them, and a proliferation of standard setters can defeat the purpose at which each aims. There is the Accounting and Auditing Organization for Islamic Financial Institutions (AAOIFI); International Islamic Financial Markets (IIFM); the Islamic Liquidity Management Corporation (ILMC), and the Islamic Financial Services Board (IFSB).

Yet the World Bank experts are hopeful; they see evidence of “convergence in some of the issues.” They don’t give examples, but move on to the issue of insolvency.

The questions that center around the issue of insolvency arise because sukuk are generally asset-backed instruments, and these questions put at issue the nature of the backing.

There is both a practical and a theological component to this. In practical terms potential investors will want to know whether the sukuk investors have a senior claim over the assets in the event of a default, under the laws of the relevant jurisdictions.

In theological terms, the possibility of insolvency raises disputes, these authors say, between more or less “purist” readings of Islamic finance. According to the purists, a “more true” sukuk would be one in which the investors have a direct claim against the assets and thus need not receive a guarantee from the obligor. But as we’ve mentioned above, much of the market is dominated by sovereign issuers, and sovereigns typically restrict private claims against government assets.

Then there is illiquidity: “Sukuk are structured products that by nature tend to have limited liquidity,” these authors observe. Some of the structures, such as sukuk al-salam [based on a forward contract for a fungible commodity] cannot be traded, for reasons that go to the heart of Islamic-finance principles. To trade salam claims makes of them “debt against advanced payment, which is inconsistent with Sharia principles.”

The tradability, and thus the liquidity, of mudharaba or musyaraka [respectively, a partnership interest with other investors, and a joint venture with the obligor] depend upon the specifics of the structure used, one of the many levels “of design challenge for sukuk and for market development generally.”

Money Markets

The World Bank economists suggest, among much else, that it may be possible for market forces to work around these impediments if sukuk issuances occur within the context of well-functioning money markets, which allow financial institutions to manage short-term liquidity issues and finance longer-term positions.

The bad news here is that the creation of Sharia-compliant money market instruments suffer from the same problems, especially the lack of standardization, observed above. But the economists praise the good work that the IIFM in particular has done in this area, devoting “significant work and research to building money market products that can be widely accepted by Islamic financial investors.”